Internet Protocol

The Internet Protocol (IP) is a core protocol in the Internet protocol suite responsible for delivering data packets from a source to a destination across network boundaries. It operates at the Network Layer (Layer 3) of the OSI model and is designed to address, route, and transfer data efficiently in a packet-switched network.

Features of IP

- Connectionless Protocol:

- IP is a connectionless protocol, meaning it does not establish a dedicated connection between the sender and receiver before transmitting data.

- Packet Switching:

- Data is divided into smaller units called packets, each transmitted independently and may take different routes to the destination.

- Addressing:

- Each device on a network is identified by a unique IP address (logical address), enabling proper routing.

- Best-Effort Delivery:

- IP does not guarantee the delivery of packets. It relies on higher-layer protocols (e.g., TCP) for reliability.

- Routing:

- Determines the best path for packets to travel through interconnected networks using routers.

- Fragmentation and Reassembly:

- Large packets are broken into smaller fragments for transmission and reassembled at the destination.

- Scalability:

- IP is designed to support networks of various sizes, from local networks to the global Internet.

- Protocol Independence:

- IP can work with a variety of transport-layer protocols like TCP, UDP, and ICMP.

Versions of IP

The two primary versions of IP in use today are IPv4 and IPv6.

IPv4 (Internet Protocol Version 4)

Overview:

- IPv4 is the fourth version of IP and was the first widely deployed protocol for network communication.

- It uses a 32-bit address format.

Features:

-

Address Format:

- IPv4 addresses are written in dot-decimal notation, e.g.,

192.168.1.1. - Supports approximately 4.3 billion unique addresses.

- IPv4 addresses are written in dot-decimal notation, e.g.,

-

Header:

- Contains fields like source address, destination address, version, and time-to-live (TTL).

- Header size: 20 bytes (minimum).

-

Protocol Support:

- Works with protocols like TCP, UDP, and ICMP.

-

Fragmentation:

- Supports packet fragmentation to fit smaller MTUs.

-

Broadcasting:

- Supports broadcast communication for sending packets to all devices in a network.

-

Address Exhaustion:

- IPv4 addresses are nearly exhausted, leading to the development of IPv6.

IPv6 (Internet Protocol Version 6)

Overview:

- IPv6 was developed to address the limitations of IPv4, particularly address exhaustion.

- It uses a 128-bit address format.

Features:

-

Address Format:

- IPv6 addresses are written in hexadecimal notation, separated by colons, e.g.,

2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334. - Supports approximately 340 undecillion (3.4 × 10³⁸) unique addresses.

- IPv6 addresses are written in hexadecimal notation, separated by colons, e.g.,

-

Header:

- Simpler and more efficient compared to IPv4.

- Header size: 40 bytes (fixed).

-

No Fragmentation:

- Fragmentation is handled by the source device, not routers, improving efficiency.

-

No Broadcasting:

- Uses multicast and anycast instead of broadcasting, reducing unnecessary traffic.

-

Built-In Security:

- Includes IPSec for authentication and encryption.

-

Auto-Configuration:

- Supports automatic address configuration using stateless address autoconfiguration (SLAAC).

-

Improved QoS (Quality of Service):

- Includes flow label fields for better handling of real-time traffic like video and voice.

Key Differences Between IPv4 and IPv6:

| Feature | IPv4 | IPv6 |

|---|---|---|

| Address Size | 32-bit | 128-bit |

| Address Format | Dot-decimal (e.g., 192.168.1.1) | Hexadecimal (e.g., 2001:0db8::1) |

| Number of Addresses | ~4.3 billion | ~340 undecillion |

| Header Size | Variable (20-60 bytes) | Fixed (40 bytes) |

| Security | Optional (via IPSec) | Mandatory (IPSec included) |

| Broadcasting | Supported | Not supported |

| Fragmentation | Supported at routers | Handled by the source device |

| Deployment | Widely used | Gradually replacing IPv4 |

IP Packets

An IP Packet is the fundamental unit of data that is transmitted across a network using the Internet Protocol (IP). It contains all the information required for routing and delivering data between devices across a network, including the source and destination IP addresses.

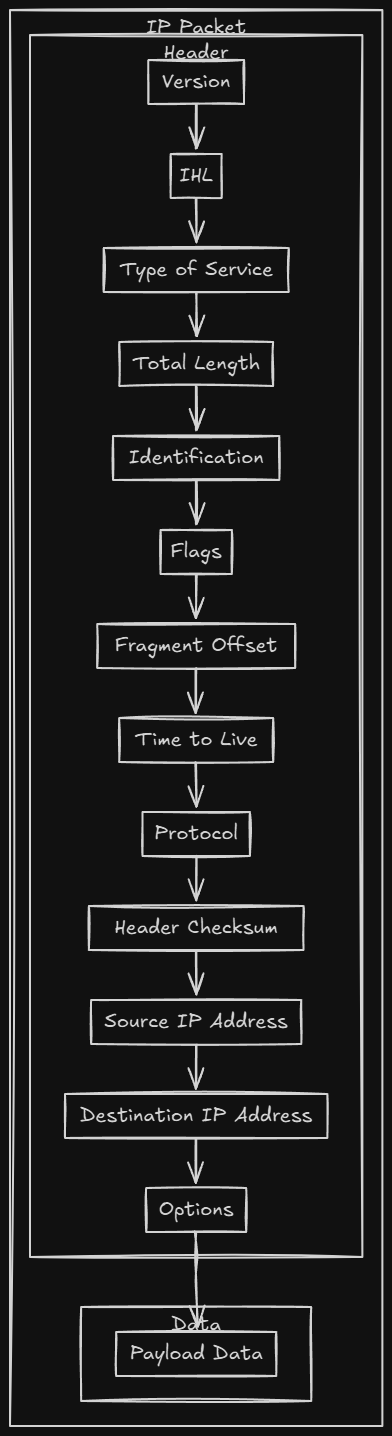

Structure of an IP Packet

An IP packet consists of two main parts:

- Header: Contains metadata about the packet, such as addressing and routing information.

- Payload: Contains the actual data being transmitted (e.g., part of a file, an email, or a web page).

IP Packet Header

The header is crucial for ensuring that packets are routed correctly and arrive at their intended destination. Its structure varies between IPv4 and IPv6.

IPv4 Header Structure

The IPv4 header is at least 20 bytes long and can extend up to 60 bytes if options are included.

| Field | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Version | 4 bits | IP version number (always 4 for IPv4). |

| Header Length | 4 bits | Length of the header in 32-bit words. |

| Type of Service (TOS) | 8 bits | Specifies priority and QoS requirements. |

| Total Length | 16 bits | Entire packet size (header + payload) in bytes. |

| Identification | 16 bits | Identifies fragments of a single packet. |

| Flags | 3 bits | Controls fragmentation. |

| Fragment Offset | 13 bits | Position of this fragment in the original packet. |

| Time-to-Live (TTL) | 8 bits | Limits the packet’s lifespan (measured in hops). |

| Protocol | 8 bits | Identifies the protocol used in the payload (e.g., TCP, UDP). |

| Header Checksum | 16 bits | Error-checking for the header. |

| Source Address | 32 bits | IP address of the sender. |

| Destination Address | 32 bits | IP address of the receiver. |

| Options (Optional) | Variable | Additional information for specific purposes (e.g., security, routing). |

IPv6 Header Structure

The IPv6 header is fixed at 40 bytes in length, making it simpler and more efficient than IPv4.

| Field | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Version | 4 bits | IP version number (always 6 for IPv6). |

| Traffic Class | 8 bits | Defines priority and QoS requirements. |

| Flow Label | 20 bits | Identifies flows for QoS management. |

| Payload Length | 16 bits | Length of the payload in bytes. |

| Next Header | 8 bits | Identifies the type of the next header (e.g., TCP, UDP, or extension headers). |

| Hop Limit | 8 bits | Limits the packet’s lifespan (like TTL in IPv4). |

| Source Address | 128 bits | IP address of the sender. |

| Destination Address | 128 bits | IP address of the receiver. |

IP Packet Payload

The payload contains the actual data being transmitted. The type of payload is determined by the Protocol or Next Header field in the IP header. Common payload types include:

- TCP segments: For reliable communication (e.g., web pages, emails).

- UDP datagrams: For lightweight and fast communication (e.g., video streaming, DNS queries).

- ICMP messages: For network diagnostics (e.g., ping).

Fragmentation in IP Packets

When a packet is too large to fit the maximum transmission unit (MTU) of a network link, it is fragmented into smaller packets.

- IPv4: Routers can fragment packets, and the receiver reassembles them.

- IPv6: Fragmentation is handled by the source device, not routers.

Lifecycle of an IP Packet

- Creation:

- Generated by the source device with the appropriate header and payload.

- Transmission:

- Routed through intermediate networks toward the destination.

- Processing:

- Each router reads the header to determine the next hop.

- Delivery:

- Arrives at the destination device, where the payload is extracted.

- Reassembly (if fragmented):

- Fragments are reassembled into the original packet at the destination.

Challenges with IP Packets

- Packet Loss: Packets may be lost due to network congestion or errors.

- Out-of-Order Delivery: Packets may arrive in a different order than they were sent.

- Security Risks: Packets can be intercepted or tampered with during transmission.

- Latency: Delays in routing can affect real-time communication.

Importance of IP Packets

IP packets are the backbone of modern networking. They ensure that data can traverse diverse networks, enabling services like the web, email, video streaming, and more. Understanding IP packets is essential for network troubleshooting, optimization, and security.

ICMP (Internet Control Message Protocol)

The Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) is a supporting protocol used within IP networks for error reporting and diagnostic purposes. It operates at the Network Layer (Layer 3) and is primarily used to communicate issues related to the delivery of packets.

Key Features

- Error Reporting:

- ICMP reports errors like unreachable destinations, time exceeded, or issues with packet fragmentation.

- Diagnostics:

- Commonly used in network diagnostic tools like ping and traceroute.

- Connectionless:

- Works without establishing a dedicated connection, like IP.

- Reliability:

- Does not guarantee delivery of error messages.

- Limited Use for Data:

- ICMP is not used for transferring application data but solely for control messages.

ICMP Packet Structure

| Field | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Type | 8 bits | Specifies the type of message (e.g., Echo Request, Destination Unreachable). |

| Code | 8 bits | Provides additional context for the message type. |

| Checksum | 16 bits | Ensures the integrity of the ICMP packet. |

| Message-Specific Data | Variable | Contains information specific to the message type. |

Common ICMP Message Types

| Type | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (Echo Reply) | 0 | Response to a ping request. |

| 3 (Destination Unreachable) | 0–15 | Indicates the destination cannot be reached. |

| 8 (Echo Request) | 0 | Used to test network connectivity (ping). |

| 11 (Time Exceeded) | 0 or 1 | Indicates that the packet's TTL expired. |

PING

PING (Packet Internet Groper) is a network diagnostic utility that uses ICMP to test the reachability of a host on a network and measure the round-trip time (RTT) for messages.

How It Works

- The source sends an ICMP Echo Request message to the destination.

- If the destination is reachable, it responds with an ICMP Echo Reply.

- The tool calculates:

- RTT: The time taken for a message to travel to the destination and back.

- Packet Loss: Percentage of packets lost during transmission.

Features

- Connectivity Testing:

- Verifies if a host is reachable.

- Performance Metrics:

- Measures latency and packet loss.

- Simple Syntax:

- Example:

ping www.example.com.

- Example:

Output Example

PING www.example.com (93.184.216.34): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 93.184.216.34: icmp_seq=0 ttl=56 time=12.3 ms

64 bytes from 93.184.216.34: icmp_seq=1 ttl=56 time=11.8 ms

--- www.example.com ping statistics ---

2 packets transmitted, 2 received, 0% packet loss, time 1001ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 11.8/12.0/12.3/0.3 ms

TraceRoute

TraceRoute is a diagnostic tool that maps the route packets take from a source to a destination, identifying each hop along the way.

How It Works

- TraceRoute sends a series of packets with incrementing Time-To-Live (TTL) values.

- Each router along the path decrements the TTL. When TTL reaches 0, the router sends an ICMP Time Exceeded message back to the source.

- By analyzing these messages, TraceRoute determines the path and delay for each hop.

Key Features

- Path Discovery:

- Identifies intermediate routers between the source and destination.

- Latency Measurement:

- Measures delay at each hop.

- Diagnostic Information:

- Helps identify bottlenecks or failed hops in the network.

TraceRoute Command Example

traceroute www.example.com

1 192.168.1.1 (192.168.1.1) 1.032 ms 0.895 ms 0.765 ms

2 10.10.0.1 (10.10.0.1) 2.345 ms 2.213 ms 2.087 ms

3 93.184.216.34 (93.184.216.34) 11.456 ms 11.312 ms 11.276 ms

Use Cases

- Detecting network routing issues.

- Identifying latency at specific hops.

- Diagnosing unreachable hosts.

Comparison of PING and TraceRoute

| Feature | PING | TraceRoute |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Tests connectivity and measures RTT. | Maps the path packets take to a destination. |

| Protocol Used | ICMP Echo Request/Reply. | ICMP Time Exceeded and optionally UDP/TCP. |

| Output | Reachability and round-trip time. | List of hops with latency information. |

| Use Case | Quick connectivity checks. | Detailed network route analysis. |

ARP (Address Resolution Protocol)

The Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) is a protocol used to map IP addresses (Network Layer addresses) to MAC addresses (Data Link Layer addresses) within a local network. This mapping is essential for devices to communicate over Ethernet-based networks (e.g., LANs) where communication occurs using MAC addresses, but IP addresses are used for routing.

ARP is crucial because, even though devices use IP addresses to send data packets, actual delivery is based on the MAC address of the device.

ARP Functionality

When a device on the network needs to send data to another device within the same local network, it must first determine the MAC address associated with the destination device’s IP address.

- ARP Request:

- The device sends a broadcast message to all devices on the local network. This message contains the target IP address, asking for the corresponding MAC address.

- ARP Reply:

- The device with the matching IP address responds directly to the sender with its MAC address.

- This reply is sent as a unicast message, so only the requesting device receives it.

- Cache:

- After receiving the ARP reply, the requesting device stores the IP-to-MAC mapping in its ARP cache for future use.

- The ARP cache stores this mapping for a specific period before it expires and needs to be refreshed.